Technological advances have led to the emergence of new economic models in recent years, especially the digital economy. However, tax regulation does not advance at the same speed as technological advances, which cause new business forms and new tax challenges. One of these new fiscal challenges is the metaverse, which currently lacks regulation and is in a phase of development and economic expansion.

The purpose of this blog is to discuss existing tax regulation applicable to the metaverse, analyse the business structure that characterizes businesses located in the metaverse and consider whether the current international tax rules provide a solution.

What is the metaverse?

The metaverse can be defined as a virtual space in which users can interact with other connected users, proposing a parallel and virtual reality where they can enjoy experiences such as attending concerts or exhibitions or carry out transactions, for example, buying clothing or other elements for an avatar. In this way, the metaverse proposes a virtual reality with a higher degree of interaction than conventional digital platforms, a superposition of reality transferred to a virtual world, which allows for new approaches and capabilities.

With all these new concepts, realities and the possibility of new business models focused on these technological advances, the question arises whether international tax law is prepared for the metaverse and the economics models situated in this new virtual reality.

Current regulations and new proposals

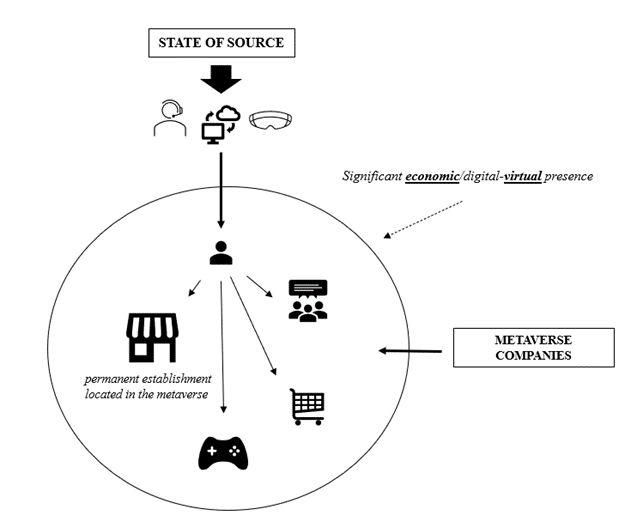

The traditional concept of permanent establishment (PE) was not adapted to new economics models, specifically to the digital economy[1]. For this reason, new taxation instruments that aim at taxing the digital economy and its multinational companies appeared. An example of this are the concepts of significant economic presence (OECD) and the concept of significant digital presence (EU). In general lines, these proposals attribute a taxing right to the state of source through a new tax nexus, which is based principally on the participation of users, marketing and business contracts and the revenues obtained from the supply of digital services.

However, the current regulation and the new proposals are focused on providing a solution to the problem of the digital economy, repeating, once again, the error of not going far enough to be able to face new technological and economic advances. First, the concept of permanent establishment gave a solution to the necessities of a time marked by an expansion and globalization of the economy; then, new concepts – significant economic/digital presence – (belatedly) try to solve the challenge of the digital economy; now it is necessary not to repeat the same error and adapt on time to a new reality and technological advances. But can the existent regulation and proposals give a solution to new technological advances and its business models, for example, businesses focused on the metaverse?

Permanent establishment and significant economic/digital presence applied to the metaverse. An opportunity to arrive on time?

Within the metaverse users can enjoy a series of experiences and acquire different goods or services. For example, the metaverse allows to acquire virtual land or digital constructions, go to stores or walk through a certain city like in real life. Thus, a certain fixity emerges from such digital assets or NFTs[2] as they are in a specific place in each metaverse. Therefore, the question that must be analyzed is: can a PE be found within the metaverse? A fixed place of business within a virtual reality? The answer must be yes: we can find a permanent establishment in a virtual reality, we can find a company that operates through a fixed place of business in the metaverse, similar to a conventional and physical store -think about a fashion brand that offers its products for avatars in a specific place in the metaverse[3]– and in this way find different permanent establishments (one located in real life and another in a parallel and virtual reality) but that share the same characteristics and essence.

The next step is to attribute a right of taxation over the particular metaverse, that is, to locate the metaverse in a certain jurisdiction in order to tax the economic returns obtained in such territory. The proposals for the concepts of significant economic/digital presence can be good options to continue work and develop not only a new taxation nexus based on the digital economy but also on new technological innovations and new business models, in this case, new solutions for economic models based on the metaverse.

Business structure and application of existing concepts

The first problem determining the different countries the company that develops a certain metaverse, that is, the company that obtains economic returns from the virtual space operates. The (physical) server that gives the necessary resources to provide access to a specific virtual space will hardly be a good indicator to establish the different countries in which the technological company operates, for example, as there could be more than one server involved and servers may be located in different territories. Moreover, the company could obtain returns in a territory without the presence of any server, hire contract server services from an external company or locate the servers in territories with low or no taxation and with no exchange of information.

Hence, the tax nexus raised by the concepts of significant economic/digital presence may be a better option. Think, for example, of the tax nexus consisting of the level of income or profits obtained in a specific state of source or the number of users of the metaverse located in a specific state. However, current concepts are essentially focused on the digital economy, as well as the provision of digital services. Specifically, the concept of significant digital presence raises assumptions that do not fully fit with the services that make up the metaverse, since virtual services are different from digital services. While the concept of significant economic presence raises a more general proposal based on the economic returns generated by a digital/virtual company without a physical presence in a specific state (for this reason, it can be considered an appropriate nexus for the economy of the metaverse), the concept of significant digital presence is more specific and refers strictly to the presence of a digital company that provides digital services and that acts without any physical presence in the state of source. Therefore, if we observe the definitions given by the Directive that proposes such concepts of significant digital presence[4], no concept can be accurately assimilated to the services that encompass the metaverse.

However, there may be some applicability of the concepts of significant economic/digital presence and the concept of permanent establishment in the field of the metaverse and its economy as long as there is an adaptation referring to the virtual services that can be found in the metaverse and its economic models. In the case of the concept of significant digital presence, the definitions should be expanded in order to not only cover digital services, but also virtual services, i.e., services that are located online. In the case of the proposal of significant economic presence, its further development has to focus on including the greatest number of digital and virtual services that current technological advances propose. Finally, given a tax nexus that can tax the metaverse, the concept of PE can be an ideal element to tax businesses located in the metaverse, specifically to be able to determine the level of business that this company located in the metaverse has in a specific state of the source. From this PE, a relationship can be established between the users of a specific state and the company that operates in a certain metaverse, in order to determine if this company really operates in the state of the corresponding source and the level of income that should be taxed.

Conclusions

The work already begun within the framework of the OECD and the European Commission, as well as the existing tax concepts, must meet in time the tax challenges that technological innovations pose. The fact that the metaverse is not as big as it could be in terms of economic importance implies that tax regulation could arrive in time, an unprecedented fact as far as international taxation is concerned, which is accustomed to arriving late and, sometimes, wrongly.

[1]HERMOSÍN ÁLVAREZ, M.: «Permanent establishment. The crisis of the article 5 OECD MC in the digital economy», Crónica Tributaria, núm. 180/2021, 2021, p. 101: «The concept of permanent establishment is a good example since it has not been adapted to this new economy».

[2] For example, VIJAYAKUMARAN, A. defines NFTs (Non-Fungible Token) as: «NFT represents a data unit in a blockchain ledger where each NFT represents a unique digital item that is not interchangeable. NFTs can be used to represent digital files such as art, audio items, video items, tweets and even a video game-based avatar. While digital files are easily reproducible in multiple numbers, NFTs representing them are traced on their underlying blockchain, providing buyers with proof of ownership». In VIJAYAKUMARAN, A.: «NFTs And Copyright Quandary», JIPITEC, No. 12, 2021, p. 404.

[3] There are many commercial brands that already operate in the metaverse, for example, among others, Gucci, Prada or Louis Vuitton (https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2023/02/09/luxury-fashion-meets-immersive-commerce-luxury-in-the-metaverse-era/; https://www.ft.com/content/d4c3d51f-4568-400e-8ca9-7706539d9cae).

[4] The Proposal for a Council Directive laying down rules relating to the corporate taxation of a significant digital presence, defines and lists a series of digital services (article 3.5), as well as its annex II, among which there cannot be found a definition or example that fits perfectly with the virtual service offered by the metaverse. Available in: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:3d33c84c-327b-11e8-b5fe-01aa75ed71a1.0017.02/DOC_1&format=PDF .