By Dirk Broekhuijsen, Ezgi Arik, and Irma Mosquera

Following the UN General Assembly resolution 77/244, the Secretary General of the United Nations called for inputs from relevant stakeholders on a report on “Promotion of inclusive and effective tax cooperation at the United Nations”. Read below a reproduction of the letter sent by Dirk Broekhuijsen, Ezgi Arik, and Irma Mosquera on 9 March as as response to the call. You can also download the lettter as pdf.

Reference: Public input “Promotion of inclusive and effective tax cooperation at the United Nations.”

Date: 9 March 2023

Authors: dr. D.M. Broekhuijsen; E. Arik Önal LLM and prof. dr. I.J. Mosquera Valderrama

Dear Secretary-General,

By means of this letter and annex, we want to provide you with our comments as regards the resolution adopted by the General Assembly on the “Promotion of inclusive and effective tax cooperation at the United Nations.”

Our comment is divided in four parts: (1) The effort and aims of the resolution and the need for a coordinated institutional setting; (2) Experience with the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent BEPS (MLI); (3) the form and contents of an instrument or framework to strengthen the international cooperative effort in international tax matters and (4) our conclusion and suggestions.

- The effort and aims of the resolution and its Institutional Setting

Efforts and aims of the Resolution

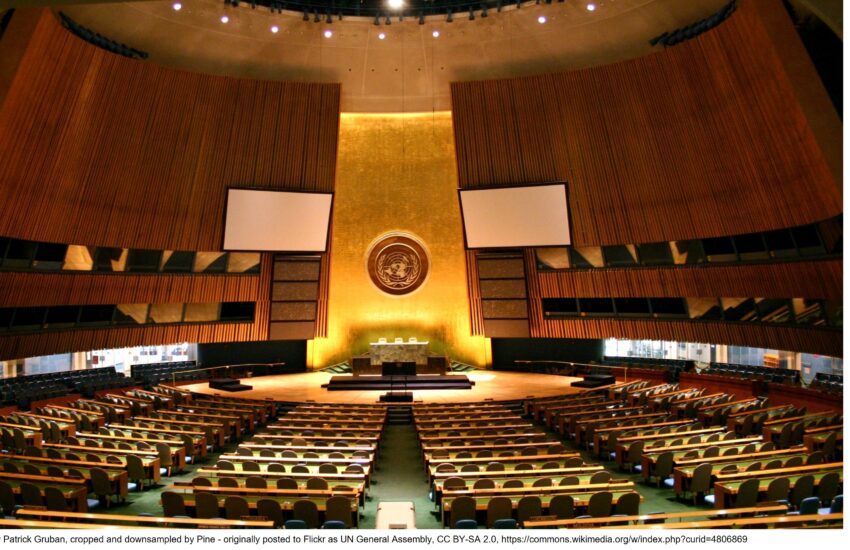

The UN Resolution reaffirms earlier international commitments to scale up international tax cooperation, fight illicit financial flows and combat aggressive tax avoidance and evasion. It decides to begin intergovernmental discussion at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on ways to strengthen the inclusiveness and effectiveness of international tax cooperation, including the possibility of developing an international tax cooperation framework or instrument that is developed and agreed upon through a United Nations intergovernmental process.

One of the most important elements in the design of any framework or instrument is to have clear goals and, in this case, for taxation, the above-mentioned framework or instrument should focus on the need to achieve international tax cooperation, to tackle tax avoidance and tax evasion. These have been the goals that tax treaties, and international tax standards (exchange of information, BEPS) have referred to, when dealing with taxation.

The UN Resolution, by referring to non-tax goals, such as illicit financial flows, although relevant, may deviate the attention of the instrument or framework to other initiatives already developed by the United Nations. For instance, the work carried out by the Task Force on the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows coordinated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)—the joint custodians of SDG Indicator 16.4.1 on illicit financial flows.[1]

Therefore, we question the relevance of the Resolution’s adherence to fighting illicit financial flows within the context of strengthening international tax cooperation.

Furthermore, the Resolution points out that illicit financial flows adversely affect financial transparency, financial integrity, and sustainable development, along with others. All these areas are indeed crucial. Nevertheless, it is questionable as to whether these align with the general goals of the UN. As mentioned in the UN Charter, the UN is an inter-governmental organization aiming to maintain broad concepts of peace and security among nations, mainly with an individual-oriented and rights-based focus. Accordingly, instead of financial perspectives, we had expected to see more concerns about individual human rights and freedoms in the UN international tax discourse, as well as their link to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals. For instance, Goal 17 Revitalizing the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development with targets such as domestic resource mobilization, capacity building, South-South and Triangular Cooperation, and Policy Coherence.

Within the context of development,[2] the Resolution focuses on economic development rather than social and cultural development. Obviously, achieving economic growth and contributing to the development of the world economy, to economic expansion and to the expansion of multilateral, non-discriminatory world trade, is an important goal.[3] But it is not the only development goal that needs to be addressed.

In fact, the UN is best placed to focus on other development goals such as social and cultural development. International tax practices such as BEPS may adversely affect social and cultural development by preventing individuals from reaching education, health, or adequate housing due to limited revenue collection, especially in developing countries. Despite all these development-related concerns, there is no reference to human rights or justice in the UN Resolution. Accordingly, we suggest the UN not to lose out of sight the aim of immediate human rights considerations of those practices.

Institutional Setting

The achievement of the UN Resolution Goals requires thinking about the governance for decision making as well as the need for a coordinated approach among existing institutions (UN Tax Committee, OECD, WB, IMF, UNDESA, UN FACTI Panel, among others). In our view, the role of the UN Tax Committee, UNDESA, UNDP and the UN FACTI Panel are relevant for the success of the instrument or framework.

In the past, one of the authors of this letter has already proposed to upgrade the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters “to a genuinely intergovernmental body for meaningful and authoritative political discussion. This political upgrade will require a concomitant strengthening of the Financing for Development Office of the UN Department for Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA), so that it can serve as a vital and dynamic secretariat for the new UN Tax Committee”.[4]

Therefore, when discussing the content of the instrument or framework, we encourage the UN to also discuss the institutional setting which should be coordinated among all relevant existing institutions.

- The experience with the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent BEPS (MLI)

The MLI is the first world-wide effort of multilateralism in international tax law. It provides an important lesson for establishing an instrument or framework for international cooperation. Most importantly, current state of affairs as regards participation points at legitimacy deficiencies as regards international tax cooperation.

In our view, the MLI lacks a fair and robust forum for international continuous discussions on international tax law. It focuses mainly on the short term (i.e., implementation) of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project, whose outcomes have been decided upon by means of mostly an administrative (non-legal) decision-making process within the auspices of the OECD/G20. It is by reason of this context, that we consider the rate of signature and ratification of the MLI by non-EU and non-OECD member states unsatisfactory (cf. Annex, Table 1 and Table 2).

Indeed, a classic “broader-deeper” tradeoff of multilateral negotiations seems to show: deeper agreements may indeed be necessary and desirable for the field of international taxation, but may come at the cost of broad support, particularly when support is demanded of states who have had little influence in establishing core commitments.

Consequently, the MLI experience shows that international cooperation in the international tax field must be seen in the long term. This requires thinking about the process of international tax cooperation itself, rather than its material outcomes.

- The form and contents of an instrument or framework to strengthen the international cooperative effort in international tax matters

The Assembly’s resolution points at establishing a treaty in which collective action problems of international tax law (e.g., tax arbitrage, tax evasion) are “managed” by means of fair legally binding procedure. Indeed, an effective multilateral cooperative instrument enshrines three elements: (i) the organization of continuous interaction between participants; (ii) inclusive and equal participation and (iii) the use of legal procedural norms (rather than informal rules or political commitments).

Continuous interaction

In indefinitely iterated forms of cooperation, participants may come to weigh the value of long-term cooperation against short-term payoffs of individual, non-cooperative strategies. Within this tradeoff, states may, in other words, reflect on the benefits of durable cooperation. This may lead to better and deeper cooperative outcomes over time.

International tax law is primarily formed of lasting and interdependent interstate relationships. Regardless of states’ different interests as regards distributive outcomes, a common interest on cooperating on international tax rules exists. This most predominantly shows in relation to tackling tax avoidance. It may hence also work for the objectives of the UN Resolution, particularly when these aims are formulated more precise (i.e., see previous section).

As a result, international tax law seems well-suited for a procedural framework that ensures continuous cooperation, for instance by having states meet every year and at the same place.

Inclusive and equal participation

It is generally accepted that procedural legitimacy (most importantly: equality and inclusivity in rule making and agenda-setting) enhances participants’ willingness to accept and comply with international law.[5] Moreover, evolutionary “processes of norm development” work best in settings where ‘learning’ can take place.[6] As teachers know, learning requires a safe environment, in which students are treated equally and where everyone is included.

As a result, international cooperation requires equal and inclusive discourse, such that knowledge may be gathered and shared, and trust may be built among participants. In this way, problems may be solved by gradually changed norms; participants may be genuinely persuaded by others rather than coerced. It means that procedural legitimacy lies at the heart of cooperation effectiveness.

Legal Norms

These requirements of procedural legitimacy must not be based on non-binding or political commitment. Instead, it is its binding legal form that matters most. The parliamentary process required to establish legally binding norms conveys important information to other participants about a state’s preferences as regards a norm and about (the reliability of) a state’s level of commitment to that norm. These, in turn, may be scrutinized by others.

Moreover, information about a state’s level of commitment may be generalized to a state’s reputation on the international level. Finally, a state’s failure to comply with binding rules that apply to it, must be explained. As it is often possible to distinguish good legal argument from bad, it makes legal norms on the international level stronger and more durable than non-binding alternatives.

When tax lawyers think about legally binding international tax rules, they think about material (distributive) tax rules. But the arguments above also hold for procedural legal norms. Clear and fair procedure underlies the legitimacy of international legislative outcomes. Binding rules facilitating inclusive and equal debate, i.e., help the cooperative effort.

An example: the framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC)

The best example of such a “managerial” treaty fulfilling these three elements is the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), drafted to curb the emission of greenhouse gasses. Although climate change is politically very complex, it is in some respects comparable to the “cooperation game” of international taxation.[7]

And even though the UNFCCC and its “COPs” have been criticized for lacking outcomes, the fact is that a form of agreement is in place, in which practically the whole world (i.e., it enjoys universal participation) comes together at specific points in time and place, drawing the world’s attention to the problems it aims to address.

In our view, it may serve as the prime example in finding directions for thinking on a cooperative instrument for international tax law.

- Conclusion

By means of a conclusion, we would like to suggest, firstly, to be more precise in formulating the aims and effort of the UN Resolution and to provide for a coordinated institutional setting. In doing so, the UN should not lose out of sight the aim of immediate human rights considerations of those practices.

Secondly, we suggest looking at the experience with the MLI. Why is state participation to the MLI by non-western economies falling short? We point at legitimacy problems underlying the cooperative effort. Thirdly, we suggest installing fair and inclusive legally binding procedural commitments by means of which continuous cooperative interaction on international tax law’s collective action problems is organized. The design of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change may provide a good point of departure.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. D.M. Broekhuijsen

Lecturer, Leiden Law School, Leiden University

E. Arik Önal LLM

Research & Teaching Associate, Koç University

PhD Candidate, Leiden Law School, Leiden University

Prof. dr. I.J. Mosquera Valderrama

Professor of Tax Governance, Leiden Law School, Leiden University

Lead Researcher ERC funded project Global Tax Governance in International Tax Law Making (GLOBTAXGOV)

Jean Monnet Chair Holder EU Tax Governance (EUTAXGOV)

Annex: MLI participation

Table 1: MLI signatory and ratifying states, by World Bank income category[8]

| Signatories | Ratifiers | ||||

| Developed | High income | 55 | 56,1% | 53 | 67,1% |

| Upper middle income | 25 | 25,5% | 14 | 17,7% | |

| Developing | Lower middle income | 17 | 17,3% | 9 | 11,4% |

| Low income | 1 | 1,0% | 1 | 1,3% | |

| # states in continent | Signatories | % of states in continent | Ratifiers | % of states in continent | |

| Europe | 44 | 44 | 100 | 42 | 95 |

| Asia | 48 | 24 | 50 | 19 | 40 |

| South America | 12 | 6 | 50 | 3 | 25 |

| North America | 23 | 7 | 30 | 5 | 22 |

| Oceania | 14 | 4 | 29 | 2 | 14 |

| Africa | 54 | 15 | 28 | 8 | 15 |

| Total | 195 | 100 | 51 | 79 | 41 |

Table 2 : MLI signatory and ratifying states, by continent

Note that of OECD Member states, 37 out of 38 states signed the MLI.

[1] Task Force on the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows coordinated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)—the joint custodians of SDG Indicator 16.4.1 on illicit financial flows

[2] Already addressed in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and the Declaration on the Right to Development.

[3] As does e.g. the OECD. See: Convention on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Dec. 14, 1960).

[4] I.J. Mosquera Valderrama, D. Lesage and W. Lips. Tax and Development: The Link between International Taxation, The Base Erosion Profit Shifting Project and The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (Institute of Tax Law and Economics, Faculty of Law, Leiden University), no. W-2018/3. Bruges, Belgium: UNU Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies.

[5] I. Mosquera Valderrama, ‘Legitimacy and the Making of International Tax Law: The Challenges of Multilateralism’, 7 (2015) World Tax Journal 344.

[6] E.g. M. Finnemore and K. Sikkink, International Norm Dynamics and Political Change 52 International Organization 887.

[7] D.M. Broekhuijsen, A Multilateral Tax Treaty : Designing an Instrument to Modernise International Tax Law, Kluwer 2018, also available through https://hdl.handle.net/1887/57407.

[8] These tables are based on data on 31-12-2022 and drawn from M. Vergouwen, D.M. Broekhuijsen and J. Reijnen, ‘The Effectiveness of the MLI in Amending the Bilateral Tax Treaty Network: (On) the Measure of Multilateral Success’, Bulletin for International Taxation, IBFD, forthcoming 2023. Note that Table 1 does not include Jersey and Guernsey. The reason for excluding these two states is that they are absent in the overview of GDP per country (see https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-by-country/).